La protéine GFP a initialement été isolée de la méduse Aequorea victoria en 1962 par Shimomura et coll. Son gène a été cloné en 1992 par Prasher et coll.

La GFP est une protéine de 238 acides aminés, acide, compacte et globulaire, possédant une masse moléculaire de 27 kDa. De nombreux mutants de la GFP sauvage ont pu être isolés par chromatographie échangeuse d'ions ou focalisation isoélectrique. D'autre part, des mutants de la GFP présentant un gain de fonction, c'est-à-dire une augmentation de l'intensité de la fluorescence, ont été générés par différentes techniques. Ainsi, la substitution du codon sérine 65 par un codon thréonine dans le clone GFP-S65T décale la longueur d'onde d'excitation en un unique pic à 490 nm. Afin d'obtenir une expression plus importante chez les cellules humaines ou d'autres mammifères, un clone dénommé hGFP-S65T, possédant des codons " humanisés ", a été réalisé par Zolotukhin et coll. en 1996. Le gène gfp sauvage contient plusieurs codons qui ne sont pas communément utilisés chez les mammifères : plus de 190 mutations silencieuses y ont ainsi été incorporées. Ces mutations permettent d'obtenir une protéine 35 fois plus fluorescente que la GFP sauvage et 5 à 10 fois plus exprimée dans les cellules de mammifères. L'expression endogène ou hétérologue de la GFP ne requiert l'addition d'aucun groupe prosthétique (protéines, substrats ou co-facteurs d'Aequorea) pour être fluorescente. Elle acquiert ses propriétés de fluorescence par un mécanisme autocatalytique de formation du fluorophore. La GFP a été exprimée de manière hétérologue dans des cellules et organismes aussi divers que les bactéries, les levures, les cellules eucaryotes animales et végétales.

Introduction

Durant l’année 2000, un professeur d’esthétique à l’université de Chicago, Eduardo Kac, a demandé à des scientifiques d’un laboratoire de biotechnologie (2) de modifier génétiquement un lapin avec un gène de méduse. Alba, la lapine résultant de cette manipulation génétique possédait la particularité de renvoyer sous la lumière ultra violette une faible lueur vert fluorescent.

Durant l’année 2000, un professeur d’esthétique à l’université de Chicago, Eduardo Kac, a demandé à des scientifiques d’un laboratoire de biotechnologie (2) de modifier génétiquement un lapin avec un gène de méduse. Alba, la lapine résultant de cette manipulation génétique possédait la particularité de renvoyer sous la lumière ultra violette une faible lueur vert fluorescent.

Précisons bien que les intentions de Kac étaient de nature artistique : il escomptait en effet s’exposer en compagnie de l’animal en question dans une sorte de « tableau domestique » en France.

« L’art transgénique crée des êtres vivants uniques. » Kac dixit

OKac publie régulièrement sur Internet (3) des articles tout à fait fumeux sur la dernière lubie artistique du moment : l’art transgénique. À grand renfort de sophismes, il tente de justifier ce qui est, en termes moraux et écologiques, profondément révoltant. Ses prétentions, tout comme celle des généticiens, sont proprement intenables. En effet, il serait, selon ses dires, en train de créer une nouvelle forme de vie « artistique » : « L’art transgénique est un art nouveau, transférant grâce à la génétique des gènes naturels ou synthétiques dans un organisme ; ainsi il permet la création d’êtres vivants uniques. »

OKac publie régulièrement sur Internet (3) des articles tout à fait fumeux sur la dernière lubie artistique du moment : l’art transgénique. À grand renfort de sophismes, il tente de justifier ce qui est, en termes moraux et écologiques, profondément révoltant. Ses prétentions, tout comme celle des généticiens, sont proprement intenables. En effet, il serait, selon ses dires, en train de créer une nouvelle forme de vie « artistique » : « L’art transgénique est un art nouveau, transférant grâce à la génétique des gènes naturels ou synthétiques dans un organisme ; ainsi il permet la création d’êtres vivants uniques. »

Le fait qu’un lapin non génétiquement modifié soit déjà un être vivant unique ne semble même pas l’effleurer.

En réalité, Kac n’a rien fait de plus que les généticiens, sans compter que ce sont ces derniers qui ont mené à bien son projet ! (4) Malgré cela, sans avoir eu à déployer un talent artistique quelconque, Kac jouit d’une audience importante. Or son seul « mérite » a été l’autopromotion de sa personne. Tel un républicain avisé, il savait que la manipulation génétique d’un lapin allait faire scandale. Ce qui ne l’empêche pas aujourd’hui de confesser bruyamment son attachement à l’animal et son intention de l’intégrer à sa famille.

Ses divagations sur Internet sont nourries de propos passionnés sur son nouveau mutant et sur la façon de traiter en toute moralité un tel artefact. Mais comme les scientifiques français hésitent à livrer l’animal aux mains de Kac, celui-ci mène aujourd’hui une bataille juridique pour sa garde, trahissant au demeurant des réflexes de propriétaire tout à fait conservateurs vis-à-vis du dernier né de sa famille, malgré la très haute moralité dont il se targue dans son site de pub.

À grand renfort de battage médiatique (5), Kac a su monter son événement artistique de façon à attirer l’attention sur sa personne. Il faut dire que son attrape-nigaud transgénique est tout à fait représentatif d’un art dont les origines sont à chercher dans le courant Dada (6) des années 1910-1920. Revisiter sans relâche l’inspiration Dada et d’autres courants du moderisme relève bien de la tradition post-moderne. (7) Pourtant, on peut se demander à quoi rime ce jeu transgénique absurde, sinon cruel, entre le lapin et la méduse.

C’est une question digne d’être posée si l’on veut remettre en cause la croyance répandue selon laquelle les artistes ne sont sincères que lorsque leurs œuvres sont dérisoires, amorales et nihilistes ? Ils ne feraient en effet – d’après ce qu’on entend souvent – que promener un miroir le long du chemin de notre civilisation. Le lignage de cet art, issu de Marcel Duchamp (8), est aujourd’hui incarné par des individus tels que Damien Hirst. Or, les travaux de ces artistes ne sont que des reproductions d’objets, de processus ou d’évènements qui nous entourent. La très médiatique Biennale de Venise est pleine à craquer de ce genre de travaux, considérés comme représentatifs de l’art contemporain.

L’approche reproductive Dada/nihiliste est bien le produit de la société de consommation moderne. On mettra certes au crédit de cet art sa franche crudité, mais c’est la crudité des clichés du photographe-reporter : dénués de toute signification, ils ne donnent à voir que superficialité et incohérence. Tout sens, toute ouverture à un ordre naturel ou cosmologique sont rejetés, et n’y demeurent que les idées philosophiques les plus rebattues.

Or ce courant artistique oublie que, dans le purgatoire d’une civilisation troublée comme la nôtre, la plupart des esprits aspirent encore au sens. Pour tout escroc artistique comme Andy Warhol avec à son actif les clichés artistiques dérisoires de son époque, on peut compter, tout au long de l’ère moderne et post moderne, nombre de bons artistes attachés à l’expression d’un sens. La plupart de ces artistes sont inconnus, mais ils ont le mérite d’exprimer les liens psychiques entre l’humanité et la nature, la communauté et le sacré. Messiaen le Messie

Certains de ces artistes, comme par exemple Messiaen, compositeur français mystique (1908-1992) sont devenus célèbres. Messiaen est une figure intéressante pour notre propos : en effet, il a pris en charge les crises de la musique du 20ème siècle symbolisée par l’usage de l’atonalité et a su incorporer cette dernière dans un ensemble plus vaste. Des canyons aux étoiles (9) évoque, dans une vision cosmologique, une nature pleine de mystère et propice à l’élévation de l’esprit. Rien de plus éloigné, on en conviendra, du lapin fluorescent.

Certains de ces artistes, comme par exemple Messiaen, compositeur français mystique (1908-1992) sont devenus célèbres. Messiaen est une figure intéressante pour notre propos : en effet, il a pris en charge les crises de la musique du 20ème siècle symbolisée par l’usage de l’atonalité et a su incorporer cette dernière dans un ensemble plus vaste. Des canyons aux étoiles (9) évoque, dans une vision cosmologique, une nature pleine de mystère et propice à l’élévation de l’esprit. Rien de plus éloigné, on en conviendra, du lapin fluorescent.

Messiaen pense que la vérité peut être enchâssée dans la structure musicale et que la transcendance existe. Kac l’exhibitionniste, en revanche, dénie toute essence, toute intégrité et toute identité, comme le montre bien la façon dont il nie l’intégrité du lapin et de la méduse. Lequel de ces deux hommes reflète-t-il mieux le monde moderne ? On serait tenté de pencher pour l’exhibitionniste.

À l’ère de la fission atomique, du génie génétique, de la sociobiologie, de l’intelligence artificielle, et de la spoliation illimitée du monde naturel, une conception nihiliste et absurde du monde ne paraît-elle pas en effet devoir s’imposer ? Ne traversons-nous pas l’âge de la fausse monnaie, des conseillers en communication, des faux-semblants en tous genres ? En ce sens, les réplications d’objets et d’événements ne sont-elles pas le seul art qui reflète fidèlement notre temps ?

Il semble que non. On touche à la vérité de l’histoire et de la vie humaine non par sa reproduction mais par son imitation, non par sa simple copie mais par son interprétation créative. La vérité de notre temps ne se retrouve pas dans ses fragments, mais dans des œuvres qui, conscientes du chaos sans nom de l’univers, en créent une image transcendante et rédemptrice grâce à un moyen langagier, sonore ou visuel.

On pourrait penser que le lapin fluorescent est une image de la vérité étant donné qu’il est une réplique du réel. Les enfants de la production de masse savent qu’un jeu vidéo est une réplique exacte d’un autre, et que toutes les espèces ont été standardisées par la monoculture et le génie génétique. Comme eux, nous croyons que la reproduction du réel est vérité et que la copie vaut l’original. La carrière d’Andy Warhol aussi bruyante que vaine, s’est construite autour de l’idée de reproduction, et cependant, la reproduction n’est qu’absence de vérité et absurdité.

En effet, qu’une voiture Nissan ressemble exactement à une autre, il s’agit là du degré zéro moral et métaphysique, tout comme l’événement artistique de Damien Hirst présentant une vache découpée en tronçons. (10) Ces entreprises-là sont tautologiques car elles produisent quelque chose qui existe déjà dans le monde réel, sans y ajouter le moindre génie intuitif, qualité que ce genre d’art méprise implicitement de toute façon.

La seule vérité que laisse voir la tautologie, c’est le caractère inhérent à notre culture matérialiste de la répétition mécanique. Cette vérité n’est pas pour autant porteuse de sens, car elle est sans rapport avec la vie. Tout art qui s’étend sur des faits triviaux finit inévitablement par leur ressembler. Les vaches découpées en tronçons, les lapins transgéniques sont victimes de cette collaboration avec le néant. Impuissants à combler le vide de sens, les artistes ne s’insurgent même pas contre lui mais se contentent d’ajouter une reproduction à ce qui a déjà été indéfiniment répété.

On y verra certes du réalisme, mais pas l’ombre d’une vérité. Nous sommes encore suffisamment proches de la nature pour savoir que cette dernière ne répète jamais à l’identique ni ne standardise. Prétendre que l’ADN reproduit à l’identique, c’est omettre les variations indéfinies pas lesquelles la nature passe d’une génération à la suivante. La réplication est précisément l’inverse des processus héréditaires, et l’art qui ne repose que sur la reproduction a quelque chose de factice, même s’il prétend se rapporter à notre monde.Victoire à la Pyrrhus

Ce courant artistique s’est inspiré de Pyrrhus, philosophe militaire (365-275 avant J.C.), dont le scepticisme extrême a été revisité avec enthousiasme par Marcel Duchamp dans la première moitié du 20ème siècle. Un tel scepticisme considère la venue au monde de la vie, de l’art, de la pensée, de la sensation et même des choses inanimées comme le fruit d’une distribution hasardeuse de quanta sans valeur et illusoires. Un objet est identique à un autre sans un cosmos où aucune essence véritable n’existe : « Tout se vaut » dit un poème post moderne.

Ce courant artistique s’est inspiré de Pyrrhus, philosophe militaire (365-275 avant J.C.), dont le scepticisme extrême a été revisité avec enthousiasme par Marcel Duchamp dans la première moitié du 20ème siècle. Un tel scepticisme considère la venue au monde de la vie, de l’art, de la pensée, de la sensation et même des choses inanimées comme le fruit d’une distribution hasardeuse de quanta sans valeur et illusoires. Un objet est identique à un autre sans un cosmos où aucune essence véritable n’existe : « Tout se vaut » dit un poème post moderne.

Cette vision du monde est répandue dans le post modernisme, dont la prétention affichée est pourtant de nous « éclairer ». Les traditions religieuses et philosophiques, particulièrement dans les cultures orientales où la transcendance est une aspiration mystique, se retrouvent récupérées et travesties par le relativisme narcissique et cynique qui caractérise les milieux artistiques branchés. Or leurs représentations trahissent une toute autre intention que l’atteinte du nirvana. Elles transpirent l’ennui, la violence gratuite et le narcissisme. Ce dernier est de la pire espèce : non pas le « oui » du « je crée dans je suis » présent dans l’art occidental le plus inspiré, mais le puéril « je veux me faire remarquer donc je suis ». S’exprime là un moi sans amour et fort différent de celui du mystique soucieux de fondre son identité dans l’universel.

L’art contemporain est fondé sur une erreur manifeste, car son mépris de l’essence ignore que les formes de la vie, de la pensée et de la sensation viennent de l’informe. Le chaos, fécond, est une vaste matrice donnant naissance aux étoiles et à la vie. Ces formes transitoires renaissent sans arrêt dans le flux cosmique, fait ignoré de nos esthètes qui dénient ce cycle, ne considérant que l’entropie, le désordre, et non les aspects créateurs de la nature.

Le moi déraciné peut-il alors exprimer authentiquement l’état précaire de la société moderne ? Il le reflètera certes mais n’aura aucune portés salvatrice, alors que dans d’autres sociétés, l’art joue un rôle rédempteur dans le cours troublé du monde, comme la tragédie grecque et certains rituels cathartiques du néolithique et du paléolithique.

À l’inverse, le clonage de l’infortunée Alba et le tronçonnage de la carcasse d’une vache ne permettent aucune catharsis et se réduisent à des lubies dénuées de toute révélation. La prétention de ces « œuvres » inspirées du courant Dada, à forger une critique de la suffisance bourgeoise et du mal-être social n’est plus défendable. L’époque où une telle prétention était encore tenable a pris fin avec la seconde guerre mondiale. Depuis, le geste artistique s’est cantonné dans un cynisme matérialiste, et le bourgeois, bien loin de s’en offusquer, s’en amuse.

Le vingtième siècle a connu de grandes contributions artistiques mais elles ne sont pas le fait d’un Kac, d’un Warhol ou d’un Hirst, tous sous l’emprise de la société de consommation. Elles proviennent d’artistes de grand talent et de grande envergure tels que Dimitri Shostakovich, la poétesse Anna Akhamatova (11), ou encore le chilien Pablo Neruda dont l’œuvre épique et visionnaire « Les Hauteurs du Machu Pichu » (12) décrit la nature et l’histoire du continent sud américain. De tels artistes et d’autres moins connus ont consacré leur vie à se battre pour notre humanité commune.

– Denys Trussel –

L'auteur est critique d’art néo-zélandais. Né en 1946, Denys Trussell est poète, essayiste, musicien et biographe. On lui doit des biographies d’A.R.B. Fairburn, poète néo-zélandais, et du peintre expressionniste anglais Alan Pearson.

Annexe

(1) Rainer Maria Rilke, « Lettres à un jeune poète, Lettre du 23 décembre 1903 ».

(2) Patrick Prunet et Louis-Marie Houdebine, directeur de recherche de l’unité de développement en biologie et en biotechnologies au centre INRA de Jouy-en-Josas. Egalement auteur de « Génie génétique, de l’animal à l’homme : un exposé pour comprendre, un essai pour réfléchir » (Paris, Flammarion 1996) et « Les animaux transgéniques » (Paris, Cachan Tec et Doc 1998).

(3) Louis-Marie Houdebine a tenu à préciser que : « Cet animal n’est pas une fantaisie de chercheur fou. Elle [Alba] est le descendant d’animaux transgéniques primaires. » Le Monde, jeudi 5 octobre 2000.

(4) Voir le site web en français et en anglais.

(5) Tout sur l'art Biotech :

– l’impressionnant dossier de presse française et étrangère sur : http://www.ekac.org/transartbiblio.html

– L'art Biotech en France : http://www.transfert.net/d52

(6) Dada : mouvement artistique fondé en 1916 à Zurich par Tristan Tzara, auteur de Sept manifestes Dada, visant à détruire toute norme esthétique. Ce mouvement a en France été repris en partie par des surréalistes tels que André Breton avec « Manifeste du Surréalisme » (1924).

(7) Olivier Cena, critique d’art à Télérama, précise dans un article intitulé « La floraison des Narcisses » que « Les plus célèbres [des artistes] utilisent les mêmes procédés qu’il y a quarante ans en se contentant de les pousser à leur paroxysme », Télérama n° 2679, 16 mai 2001.

(8) Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) a inauguré la vogue du « ready-made » en envoyant à l’Armory Show (New York) en 1917 un urinoir intitulé « Fontaine ». Ce premier événement « anti-art » a fait date.

(9) « Des canyons aux étoiles », Olivier Messiaen. Sous la direction d’Esa-Pekka Salonen, London Sinfonietta, Sony Classics.

(10) Damien Hirst a reçu le prix Turner en 1995 décerné par des représentants reconnus du milieu artistique britannique, dont le directeur de la Tate Gallery à Londres. Ce prix a récompensé son exposition « Some went mad some ran away », (Certains sont devenus fous, d’autres se sont enfuis) dont l’ « œuvre » : « Mother and child divided » présentait des vaches découpées dans le sens de la longueur et conservées dans des bacs transparents remplis de formaldéhyde.

(11) Poétesse russe (1886-1966), censurée par le Comité central, elle a laissé des poèmes et une autobiographie (« Requiem ») relatant la répression des années 1930.

(12) Pabo Neruda (1904-1973), « Les Hauteurs du Macchu Picchu », Seghers, coll. Autour du monde, 1999.

Originally published in San Francisco Chronicle, Monday, October 8, 1999, p. B1, B13.

| GFP BUNNY | ||

| Eduardo Kac My transgenic artwork "GFP Bunny" comprises the creation of a green fluorescent rabbit, the public dialogue generated by the project, and the social integration of the rabbit. GFP stands for green fluorescent protein. "GFP Bunny" was realized in 2000 and first presented publicly in Avignon, France. Transgenic art, I proposed elsewhere [1], is a new art form based on the use of genetic engineering to transfer natural or synthetic genes to an organism, to create unique living beings. This must be done with great care, with acknowledgment of the complex issues thus raised and, above all, with a commitment to respect, nurture, and love the life thus created. WELCOME, ALBA I will never forget the moment when I first held her in my arms, in Jouy-en-Josas, France, on April 29, 2000. My apprehensive anticipation was replaced by joy and excitement. Alba -- the name given her by my wife, my daughter, and I -- was lovable and affectionate and an absolute delight to play with. As I cradled her, she playfully tucked her head between my body and my left arm, finding at last a comfortable position to rest and enjoy my gentle strokes. She immediately awoke in me a strong and urgent sense of responsibility for her well-being. |  Eduardo Kac and Alba, the fluorescent bunny. Eduardo Kac and Alba, the fluorescent bunny. Photo: Chrystelle Fontaine |

Alba is undoubtedly a very special animal, but I want to be clear that her formal and genetic uniqueness are but one component of the "GFP Bunny" artwork. The "GFP Bunny" project is a complex social event that starts with the creation of a chimerical animal that does not exist in nature (i.e., "chimerical" in the sense of a cultural tradition of imaginary animals, not in the scientific connotation of an organism in which there is a mixture of cells in the body) and that also includes at its core: 1) ongoing dialogue between professionals of several disciplines (art, science, philosophy, law, communications, literature, social sciences) and the public on cultural and ethical implications of genetic engineering; 2) contestation of the alleged supremacy of DNA in life creation in favor of a more complex understanding of the intertwined relationship between genetics, organism, and environment; 3) extension of the concepts of biodiversity and evolution to incorporate precise work at the genomic level; 4) interspecies communication between humans and a transgenic mammal; 5) integration and presentation of "GFP Bunny" in a social and interactive context; 6) examination of the notions of normalcy, heterogeneity, purity, hybridity, and otherness; 7) consideration of a non-semiotic notion of communication as the sharing of genetic material across traditional species barriers; 8) public respect and appreciation for the emotional and cognitive life of transgenic animals; 9) expansion of the present practical and conceptual boundaries of artmaking to incorporate life invention.

Alba, the fluorescent bunny.

Photo: Chrystelle Fontaine

GLOW IN THE FAMILY

"Alba", the green fluorescent bunny, is an albino rabbit. This means that, since she has no skin pigment, under ordinary environmental conditions she is completely white with pink eyes. Alba is not green all the time. She only glows when illuminated with the correct light. When (and only when) illuminated with blue light (maximum excitation at 488 nm), she glows with a bright green light (maximum emission at 509 nm). She was created with EGFP, an enhanced version (i.e., a synthetic mutation) of the original wild-type green fluorescent gene found in the jellyfish Aequorea Victoria. EGFP gives about two orders of magnitude greater fluorescence in mammalian cells (including human cells) than the original jellyfish gene [2].

The first phase of the "GFP Bunny" project was completed in February 2000 with the birth of "Alba" in Jouy-en-Josas, France. This was accomplished with the invaluable assistance of zoosystemician Louis Bec [3] and scientists Louis-Marie Houdebine and Patrick Prunet [4]. Alba's name was chosen by consensus between my wife Ruth, my daughter Miriam, and myself. The second phase is the ongoing debate, which started with the first public announcement of Alba's birth, in the context of the Planet Work conference, in San Francisco, on May 14, 2000. The third phase will take place when the bunny comes home to Chicago, becoming part of my family and living with us from this point on.

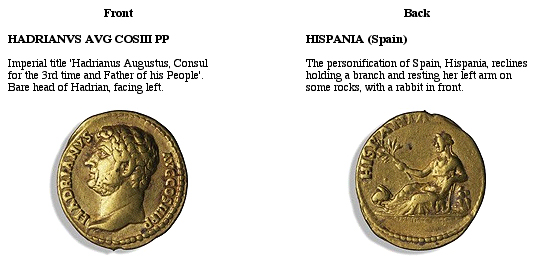

Coin issued by the Roman emperor Hadrian, AD134-8; 20mm

Hadrian reigned from 117 to 138 AD. Collection Museum of London.

The human-rabbit association can be traced back to the biblical era, as exemplified by passages in the books Leviticus (Lev. 11:5) and Deuteronomy (De. 14:7), which make reference to saphan, the Hebrew word for rabbit. Phoenicians seafarers discovered rabbits on the Iberian Peninsula around 1100 BC and, thinking that these were Hyraxes (also called Rock Dassies), called the land "i-shepan-im" (land of the Hyraxes). Since the Iberian Peninsula is north of Africa, relative geographic position suggests that another Punic derivation comes from sphan, "north". As the Romans adapted "i-shepan-im" to Latin, the word Hispania was created -- one of the etymological origins of Spain. In his book III the Roman geographer Strabo (ca. 64 BC - AD 21) called Spain "the land of rabbits". Later on, the Roman emperor Servius Sulpicius Galba (5 BC - AD 69), whose reign was short-lived (68-69 AD), issued a coin on which Spain is represented with a rabbit at her feet. Although semi-domestication started in the Roman period, in this initial phase rabbits were kept in large walled pens and were allowed to breed freely.

Humans started to play a direct role in the evolution of the rabbit from the sixth to the tenth centuries AD, when monks in southern France domesticated and bred rabbits under more restricted conditions [5]. Originally from the region comprised by southwestern Europe and North Africa, the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) is the ancestor of all domestic breeds. Since the sixth century, because of its sociable nature the rabbit increasingly has become integrated into human families as a domestic companion. Such human-induced selective breeding created the morphological diversity found in rabbits today. The first records describing a variety of fur colors and sizes distinct from wild breeds date from the sixteenth century. It was not until the eighteenth century that selective breeding resulted in the Angora rabbit, which has a uniquely thick and beautiful wool coat. The process of domestication carried out since the sixth century, coupled with ever increasing worldwide migration and trade, resulted in many new breeds and in the introduction of rabbits into new environments different from their place of origin. While there are well over 100 known breeds of rabbit around the world, "recognized" pedigree breeds vary from one country to another. For example, the American Rabbit Breeders Association (ARBA) "recognizes" 45 breeds in the U.S.A., with more under development.

In addition to selective breeding, naturally occurring genetic variations also contributed to morphological diversity. The albino rabbit, for example, is a natural (recessive) mutation which in the wild has minimal chances of survival (due to lack of proper pigmentation for camouflage and keener vision to spot prey). However, because it has been bred by humans, it can be found widely today in healthy populations. The human preservation of albino animals is also connected to ancient cultural traditions: almost every Native American tribe believed that albino animals had particular spiritual significance and had strict rules to protect them [6].

|  | |

| Ixchel and the Rabbit, North America, C.800 C.E. Ixchel is the moon goddess in Maya mythology, often depicted sitting in a moon sign holding a rabbit. | Rabbit on the moon found on pottery of the Mimbres tribe, who lived in what is now the Southwestern United States from the 9th to 12th centuries. |

"GFP Bunny" is a transgenic artwork and not a breeding project. The differences between the two include the principles that guide the work, the procedures employed, and the main objectives. Traditionally, animal breeding has been a multi-generational selection process that has sought to create pure breeds with standard form and structure, often to serve a specific performative function. As it moved from rural milieus to urban environments, breeding de-emphasized selection for behavioral attributes but continued to be driven by a notion of aesthetics anchored on visual traits and on morphological principles. Transgenic art, by contrast, offers a concept of aesthetics that emphasizes the social rather than the formal aspects of life and biodiversity, that challenges notions of genetic purity, that incorporates precise work at the genomic level, and that reveals the fluidity of the concept of species in an ever increasingly transgenic social context.

As a transgenic artist, I am not interested in the creation of genetic objects, but on the invention of transgenic social subjects. In other words, what is important is the completely integrated process of creating the bunny, bringing her to society at large, and providing her with a loving, caring, and nurturing environment in which she can grow safe and healthy. This integrated process is important because it places genetic engineering in a social context in which the relationship between the private and the public spheres are negotiated. In other words, biotechnology, the private realm of family life, and the social domain of public opinion are discussed in relation to one another. Transgenic art is not about the crafting of genetic objets d'art, either inert or imbued with vitality. Such an approach would suggest a conflation of the operational sphere of life sciences with a traditional aesthetics that privileges formal concerns, material stability, and hermeneutical isolation. Integrating the lessons of dialogical philosophy [7] and cognitive ethology [8], transgenic art must promote awareness of and respect for the spiritual (mental) life of the transgenic animal. The word "aesthetics" in the context of transgenic art must be understood to mean that creation, socialization, and domestic integration are a single process. The question is not to make the bunny meet specific requirements or whims, but to enjoy her company as an individual (all bunnies are different), appreciated for her own intrinsic virtues, in dialogical interaction.

|  | |

| Medieval rabbit. Detail from the tapestry "The Lady with the Unicorn", c. 1500. Cluny Museum, Paris. | Aztec rabbit. Shown on the back of the "Coronation Stone of Motecuhzoma II", Mexico, A.D. 1503. Art Institute, Chicago. |

One very important aspect of "GFP Bunny" is that Alba, like any other rabbit, is sociable and in need of interaction through communication signals, voice, and physical contact. As I see it, there is no reason to believe that the interactive art of the future will look and feel like anything we knew in the twentieth century. "GFP Bunny" shows an alternative path and makes clear that a profound concept of interaction is anchored on the notion of personal responsibility (as both care and possibility of response). "GFP Bunny" gives continuation to my focus on the creation, in art, of what Martin Buber called dialogical relationship [9], what Mikhail Bakhtin called dialogic sphere of existence [10], what Emile Benveniste called intersubjectivity [11], and what Humberto Maturana calls consensual domains [12]: shared spheres of perception, cognition, and agency in which two or more sentient beings (human or otherwise) can negotiate their experience dialogically. The work is also informed by Emmanuel Levinas' philosophy of alterity [13], which states that our proximity to the other demands a response, and that the interpersonal contact with others is the unique relation of ethical responsibility. I create my works to accept and incorporate the reactions and decisions made by the participants, be they eukaryotes or prokaryotes [14]. This is what I call the human-plant-bird-mammal-robot-insect-bacteria interface.

In order to be practicable, this aesthetic platform--which reconciles forms of social intervention with semantic openness and systemic complexity--must acknowledge that every situation, in art as in life, has its own specific parameters and limitations. So the question is not how to eliminate circumscription altogether (an impossibility), but how to keep it indeterminate enough so that what human and nonhuman participants think, perceive, and do when they experience the work matters in a significant way. My answer is to make a concerted effort to remain truly open to the participant's choices and behaviors, to give up a substantial portion of control over the experience of the work, to accept the experience as-it-happens as a transformative field of possibilities, to learn from it, to grow with it, to be transformed along the way. Alba is a participant in the "GFP Bunny" transgenic artwork; so is anyone who comes in contact with her, and anyone who gives any consideration to the project. A complex set of relationships between family life, social difference, scientific procedure, interspecies communication, public discussion, ethics, media interpretation, and art context is at work.

Throughout the twentieth century art progressively moved away from pictorial representation, object crafting, and visual contemplation. Artists searching for new directions that could more directly respond to social transformations gave emphasis to process, concept, action, interaction, new media, environments, and critical discourse. Transgenic art acknowledges these changes and at the same time offers a radical departure from them, placing the question of actual creation of life at the center of the debate. Undoubtedly, transgenic art also develops in a larger context of profound shifts in other fields. Throughout the twentieth century physics acknowledged uncertainty and relativity, anthropology shattered ethnocentricity, philosophy denounced truth, literary criticism broke away from hermeneutics, astronomy discovered new planets, biology found "extremophile" microbes living in conditions previously believed not capable of supporting life, molecular biology made cloning a reality.

Transgenic art acknowledges the human role in rabbit evolution as a natural element, as a chapter in the natural history of both humans and rabbits, for domestication is always a bidirectional experience. As humans domesticate rabbits, so do rabbits domesticate their humans. If teleonomy is the apparent purpose in the organization of living systems [15], then transgenic art suggests a non-utilitarian and more subtle approach to the debate. Moving beyond the metaphor of the artwork as a living organism into a complex embodiment of the trope, transgenic art opens a nonteleonomic domain for the life sciences. In other words, in the context of transgenic art humans exert influence in the organization of living systems, but this influence does not have a pragmatic purpose. Transgenic art does not attempt to moderate, undermine, or arbitrate the public discussion. It seeks to offer a new perspective that offers ambiguity and subtlety where we usually only find affirmative ("in favor") and negative ("against") polarity. "GFP Bunny" highlights the fact that transgenic animals are regular creatures that are as much part of social life as any other life form, and thus are deserving of as much love and care as any other animal [16].

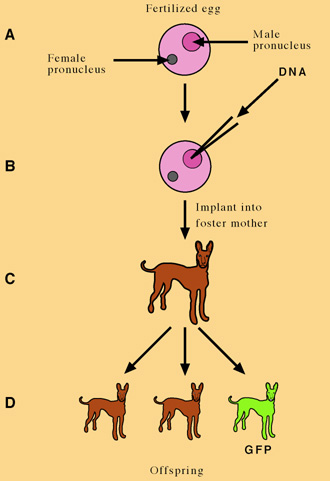

In developing the "GFP Bunny" project I have paid close attention and given careful consideration to any potential harm that might be caused. I decided to proceed with the project because it became clear that it was safe [17]. There were no surprises throughout the process: the genetic sequence responsible for the production of the green fluorescent protein was integrated into the genome through zygote microinjection [18]. The pregnancy was carried to term successfully. "GFP Bunny" does not propose any new form of genetic experimentation, which is the same as saying: the technologies of microinjection and green fluorescent protein are established well-known tools in the field of molecular biology. Green fluorescent protein has already been successfully expressed in many host organisms, including mammals [19]. There are no mutagenic effects resulting from transgene integration into the host genome. Put another way: green fluorescent protein is harmless to the rabbit. It is also important to point out that the "GFP Bunny" project breaks no social rule: humans have determined the evolution of rabbits for at least 1400 years.

|

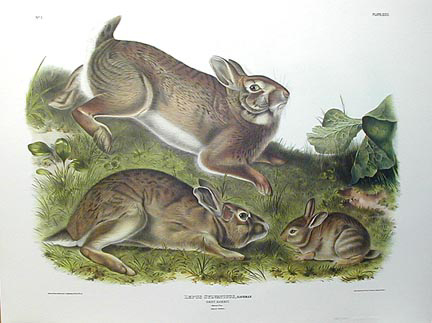

| The Grey Rabbit, from John James Audubon's Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America,1845-1848. |

As we negotiate our relationship with our lagomorph companion [20], it is necessary to think rabbit agency without anthropomorphizing it. Relationships are not tangible, but they form a fertile field of investigation in art, pushing interactivity into a literal domain of intersubjectivity. Everything exists in relationship to everything else. Nothing exists in isolation. By focusing my work on the interconnection between biological, technological, and hybrid entities I draw attention to this simple but fundamental fact. To speak of interconnection or intersubjectivity is to acknowledge the social dimension of consciousness. Therefore, the concept of intersubjectivity must take into account the complexity of animal minds. In this context, and particularly in regard to "GFP Bunny", one must be open to understanding the rabbit mind, and more specifically to Alba's unique spirit as an individual. It is a common misconception that a rabbit is less intelligent than, for example, a dog, because, among other peculiarities, it seems difficult for a bunny to find food right in front of her face. The cause of this ordinary phenomenon becomes clear when we consider that the rabbit's visual system has eyes placed high and to the sides of the skull, allowing the rabbit to see nearly 360 degrees. As a result, the rabbit has a small blind spot of about l0 degrees directly in front of her nose and below her chin [21]. Although rabbits do not see images as sharply as we do, they are able to recognize individual humans through a combination of voice, body movements, and scent as cues, provided that humans interact with their rabbits regularly and don't change their overall configuration in dramatic ways (such as wearing a costume that alters the human form or using a strong perfume). Understanding how the rabbit sees the world is certainly not enough to appreciate its consciousness but it allows us to gain insights about its behavior, which leads us to adapt our own to make life more comfortable and pleasant for everyone.

Alba is a healthy and gentle mammal. Contrary to popular notions of the alleged monstrosity of genetically engineered organisms, her body shape and coloration are exactly of the same kind we ordinarily find in albino rabbits. Unaware that Alba is a glowing bunny, it is impossible for anyone to notice anything unusual about her. Therefore Alba undermines any ascription of alterity predicated on morphology and behavioral traits. It is precisely this productive ambiguity that sets her apart: being at once same and different. As is the case in most cultures, our relationship with animals is profoundly revealing of ourselves. Our daily coexistence and interaction with members of other species remind us of our uniqueness as humans. At the same time, it allow us to tap into dimensions of the human spirit that are often suppressed in daily life--such as communication without language--that reveal how close we really are to nonhumans. The more animals become part of our domestic life, the further we move breeding away from functionality and animal labor. Our relationship with other animals shifts as historical conditions are transformed by political pressures, scientific discoveries, technological development, economic opportunities, artistic invention, and philosophical insights. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, as we transform our understanding of human physical boundaries by introducing new genes into developed human organisms, our communion with animals in our environment also changes. Molecular biology has demonstrated that the human genome is not particularly important, special, or different. The human genome is made of the same basic elements as other known life forms and can be seen as part of a larger genomic spectrum rich in variation and diversity.

Western philosophers, from Aristotle [22] to Descartes [23], from Locke [24] to Leibniz [25], from Kant [26] to Nietsche [27] and Buber [28], have approached the enigma of animality in a multitude of ways, evolving in time and elucidating along the way their views of humanity. While Descartes and Kant possessed a more condescending view of the spiritual life of animals (which can also be said of Aristotle), Locke, Leibniz, Nietsche, and Buber are -- in different degrees -- more tolerant towards our eukaryotic others [29]. Today, our ability to generate life through the direct method of genetic engineering prompts a re-evaluation of the cultural objectification and the personal subjectification of animals, and in so doing it renews our investigation of the limits and potentialities of what we call humanity. I do not believe that genetic engineering eliminates the mystery of what life is; to the contrary, it reawakens in us a sense of wonder towards the living. We will only think that biotechnology eliminates the mystery of life if we privilege it in detriment to other views of life (as opposed to seeing biotechnology as one among other contributions to the larger debate) and if we accept the reductionist view (not shared by many biologists) that life is purely and simply a matter of genetics. Transgenic art is a firm rejection of this view and a reminder that communication and interaction between sentient and nonsentient actants lies at the core of what we call life. Rather than accepting the move from the complexity of life processes to genetics, transgenic art gives emphasis to the social existence of organisms, and thus highlights the evolutionary continuum of physiological and behavioral characteristics between the species. The mystery and beauty of life is as great as ever when we realize our close biological kinship with other species and when we understand that from a limited set of genetic bases life has evolved on Earth with organisms as diverse as bacteria, plants, insects, fish, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

TRANSGENESIS, ART, AND SOCIETY

The success of human genetic therapy suggests the benefits of altering the human genome to heal or to improve the living conditions of fellow humans [30]. In this sense, the introduction of foreign genetic material in the human genome can be seen not only as welcome but as desirable. Developments in molecular biology, such as the above example, are at times used to raise the specter of eugenics and biological warfare, and with it the fear of banalization and abuse of genetic engineering. This fear is legitimate, historically grounded, and must be addressed. Contributing to the problem, companies often employ empty rhetorical strategies to persuade the public, thus failing to engage in a serious debate that acknowledges both the problems and benefits of the technology. [31] There are indeed serious threats, such as the possible loss of privacy regarding one's own genetic information, and unacceptable practices already underway, such as biopiracy (the appropriation and patenting of genetic material from its owners without explicit permission).

As we consider these problems, we can not ignore the fact that a complete ban on all forms of genetic research would prevent the development of much needed cures for the many devastating diseases that now ravage human and nonhumankind. The problem is even more complex. Should such therapies be developed successfully, what sectors of society will have access to them? Clearly, the question of genetics is not purely and simply a scientific matter, but one that is directly connected to political and economic directives. Precisely for this reason, the fear raised by both real and potential abuse of this technology must be channeled productively by society. Rather than embracing a blind rejection of the technology, which is undoubtedly already a part of the new bioscape, citizens of open societies must make an effort to study the multiple views on the subject, learn about the historical background surrounding the issues, understand the vocabulary and the main research efforts underway, develop alternative views based on their own ideas, debate the issue, and arrive at their own conclusions in an effort to generate mutual understanding. Inasmuch as this seems a daunting task, drastic consequences may result from hype, sheer opposition, or indifference.

This is where art can also be of great social value. Since the domain of art is symbolic even when intervening directly in a given context [32], art can contribute to reveal the cultural implications of the revolution underway and offer different ways of thinking about and with biotechnology. Transgenic art is a mode of genetic inscription that is at once inside and outside of the operational realm of molecular biology, negotiating the terrain between science and culture. Transgenic art can help science to recognize the role of relational and communicational issues in the development of organisms. It can help culture by unmasking the popular belief that DNA is the "master molecule" through an emphasis on the whole organism and the environment (the context). At last, transgenic art can contribute to the field of aesthetics by opening up the new symbolic and pragmatic dimension of art as the literal creation of and responsibility for life.

NOTES

1 - Kac, Eduardo. "Transgenic Art", Leonardo Electronic Almanac, Vol. 6, N. 11, December 1998. Republished in: Gerfried Stocker and Christine Schopf (eds.), Ars Electronica '99 - Life Science (Vienna, New York: Springer, 1999), pp. 289- 296. See also: Kac, Eduardo. "Genesis", in Spike/Genesis, exhibition catalogue, O. K. Center for Contemporary Art, Linz, Austria, pp. 50-55.

2 - After green fluorescent protein (GFP) was first isolated from Aequorea victoria and used as a new reporter system (see: Chalfie, M., Tu, Y., Euskirchen, G., Ward, W., Prasher, D. (1994). Green Fluorescent Protein as a Marker for Gene Expression. Science 263, 802-805) it was modified in the laboratory to increase fluorescence. See: Heim, R., Cubitt, A. B. and Tsien, R.Y. (1995) Improved green fluorescence. Nature 373:663-664; and Heim, R., Tsien, R. Y. (1996). Engineering green fluorescent protein for improved brightness, longer wavelengths and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Current Biology 6, 178-182. Further work altered the green fluorescent protein gene to conform to the favored codons of highly expressed human proteins and thus allowed improved expression in mammalian cells. See: Haas, J, Park, EC and Seed, B. (1996). Codon usage limitation in the expression of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein. Current Biology 6: 315-24. More recently, new mutations with greater fluorescence have been developed. See: Yang, Te-Tuan et al. (1998). Improved fluorescence and dual color detection with enhanced blue and green variants of the green fluorescent protein. The Journal of biological chemistry, V. 273, N. 14, p. 8212. For a comprehensive overview of green fluorescent protein as a genetic marker, see: Chalfie, Martin. Kain, Steven. Green fluorescent protein : properties, applications, and protocols (New York : Wiley-Liss, 1998). Since its first introduction in molecular biology, GFP has been expressed in many organisms, including bacteria, yeast, slime mold, many plants, fruit flies, zebrafish, many mammalian cells, and even viruses. Moreover, many organelles, including the nucleus, mitochondria, plasma membrane, and cytoskeleton, have been marked with GFP.

3 - Artist, curator, and cultural promoter Louis Bec coined the term zoosystémicien (zoosystemician) to define his artistic practice and his sphere of interest, i.e., the digital modeling of living systems. Formerly Inspecteur à la création artistique chargé des Nouvelles Technologies, Ministère de la Culture (Coordinator of Art and Technology for the French Ministry of Culture), Louis Bec was the Director of the festival Avignon Numerique (Digital Avignon), celebrated in Avignon, France, from April 1999 to November 2000, on the occasion of Avignon's status as European cultural capital of the year 2000.

4 - Louis-Marie Houdebine and Patrick Prunet are scientists who work at the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique-INRA (National Institute of Agronomic Research), France. Louis-Marie Houdebine is the Director of Research of the Biology of Development and Biotechnology Unit, INRA, Jouy-en-Josas Center, France. Among his books in French we find: Le génie génétique, de l'animal à l'homme : un exposé pour comprendre, un essai pour réfléchir (Paris : Flammarion, 1996); Les biotechnologies animales : une nécessité ou une révolution inutile (Paris : Cachan : France agricole, 1998); and Les animaux transgéniques (Paris : Cachan : Tec et Doc, 1998). In English: Transgenic Animals - Generation and Use (Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1997). Patrick Prunet is a researcher in the Group in Physiology of Stress and Adaptation, INRA, Campus de Beaulieu, Rennes, France.

5 - For an account of the history of domestication, see: Zeuner, Frederick Everard. A History of Domesticated Animals (New York : Harper & Row, 1963); Clutton-Brock, Juliet. Domesticated Animals from Early Times (London: British Museum, 1981); Caras, Roger A. A Perfect Harmony: The Intertwining Lives of Animals and Humans Throughout History (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996); Gautier, Achilles. La domestication. Et l'homme créa ses animaux.(Paris: Editions Errance, 1990); Helmer, Daniel. La domestication des animaux par les hommes préhistoriques (Paris: Masson, 1992).; and Sawer, Carl O. Agricultural Origins and Dispersals: The Domestication of Animals and Foodstuffs (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1970). For specific references on the domestication of rabbits see: Biadi, F. and Le Gall, A., Le lapin de garenne (Paris: Hatier, 1993); Bianciotto, G., Bestiaires du Moyen Âge (Paris: Stock, 1980); Brochier, J. J., Anthologie du lapin (Paris: Hatier, 1987); Le lapin, aspects historiques, culturels et sociaux.Ñ Ethnozootechnie, n° 27, 1980.

6 - Detailed information about the spiritual values of individual tribes can be found in: Gill, Sam D., Dictionary of Native American mythology (New York : Oxford University Press, 1994). See also: Hirschfelder, Arlene B., Encyclopedia of Native American religions : an introduction (New York : Facts on File, 2000). Richard Erdoes and Alfonso Ortiz (Editors). American Indian Myths and Legends (New York: Pantheon Books, 1985). A recent case that well illustrates the sacred qualities of albino animals for Native American tribes was the birth of "Miracle", the white buffalo calf. "Miracle" was born on the Heider farm, in Janesville, Wisconsin, on August 20, 1994. The announcement of Miracle's birth prompted the American Bison Association to say that the last documented white buffalo died in 1959. Miracle is held sacred by buffalo-hunting Plains Indians, including the Lakota, the Oneida, the Cherokee, and the Cheyenne. Soon after her birth, Joseph Chasing Horse, traditional leader of the Lakota nation, visited the site of Miracle's birth and conducted a Pipe ceremony there, while telling the story of White Buffalo Calf Woman, a legendary figure who brought the first Pipe to the Lakota people. Following suit, more than 20,000 people come to see Miracle, and the gate to the Heider's pasture and the trees next to it soon became covered with offerings: feathers, necklaces and pieces of colorful cloth. News of the calf spread quickly through the Native American community because its birth fulfilled a 2,000-year-old prophecy of northern Plains Indians. Joseph Chasing Horse explained in a newspaper interview that 2,000 years ago a young woman who first appeared in the shape of a white buffalo gave the Lakota's ancestors a sacred pipe and sacred ceremonies and made them guardians of the Black Hills. Before leaving, she also prophesied that one day she would return to purify the world, bringing back spiritual balance and harmony; the birth of a white buffalo calf would be a sign that her return was at hand. Owen Mike, head of the Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) buffalo clan, said in the same article that his people have a slightly different interpretation of the white calf's significance. He added, however, that the Ho-Chunk version of the prophecy also stresses the return of harmony, both in nature and among all peoples. "It's more of a blessing from the Great Spirit," Mike explained. "It's a sign. This white buffalo is showing us that everything is going to be okay." See: "Miracle", Tom Laskin, Isthmus Newspaper, Madison, Wisconsin; Nov. 25-Dec 1, 1994.

7 - In the twentieth century, dialogical philosophy found renewed impetus with Martin Buber, who published in 1923 the book I-Thou, in which he stated that humankind is capable of two kinds of relationship: I and Thou (reciprocity) and I-It (objectification). In I and Thou relations one fully engages in the encounter with the other and carries on a real dialogue. In I-It relations "It" becomes an object of control. The "I" in both cases is not the same, for in the first case there is a non-hierarchical meeting while in the second case there is detachment. See: Buber, Martin. I and Thou (New York: Collier, 1987). Martin Buber's dialogical philosophy of relation, which is very close to Phenomenology and Existentialism, also influenced Mikhail Bakhtin's philosophy of language. Bakhtin stated in countless writings that ordinary instances of monological experience--in culture, politics, and society--suppress the dialogical reality of existence.

8 - Cognitive ethology can be defined as "the evolutionary and comparative study of nonhuman animal thought processes, consciousness, beliefs, or rationality, and is an area in which research is informed by different types of investigations and explanations." See: Bekoff, Marc (1995). "Cognitive Ethology and the Explanation of Nonhuman Animal Behavior", in Comparative Approaches to Cognitive Science. J. A. Meyer and H. L. Roitblat, eds. (Cambridge, Mass. : MIT Press, 1995), 119-150. A pioneer of ethology, the Estonian zoologist Jakob von Uexküll (1864-1944) devoted himself to the problem of how living beings subjectively perceive their environment and how this perception determines their behavior. In 1909 he wrote "Umwelt und Innenwelt der Tiere", introducing the German word 'umwelt" (roughly translated, "environment") to refer to the subjective world of an organism. The book has been excerpted in Foundations of Comparative Ethology, ed. G. Burghardt (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1985). Since Uexküll emphasized the fact that signs and meanings are of the utmost importance in all aspects of biological processes (at the level of the cell or the organism), he also anticipated the concerns of cognitive ethology and biosemiotics (the study of signs, of communication, and of information in living organisms). See: Uexkull, Jacob von. Mondes animaux et monde humain : suivi de théorie de la signification (Paris : Denoël, 1984). Further contributing to the subjective world of other animals, Donald Griffin first demonstrated that bats navigate the world using biosonar, a process he called "echolocation". See: Griffin, Donald R. Listening in the dark : the acoustic orientation of bats and men (Ithaca ; London : Comstock Publishing, 1986). First published in 1958. Griffin has since contributed to cognitive ethology with many books, most notably: The Question of Animal Awareness: Evolutionary Continuity of Mental Experience. (New York : The Rockefeller University Press, 1976), Animal Thinking (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1984) and Animal Minds (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992). Another important pioneering contribution was: Nagel, T. 1974. What is it like to be a bat? Philosophical Review 83: 435-405. In this paper Nagel offered a critique of physicalist explanations of the mind, pointing out that they do not take into account consciousness, i.e. what is the actual life experience of an organism. In this paper, a classic both of cognitive ethology and consciousness studies, Nagel reminds us that what science professes to be objective accounts inevitably omit points of view. In recognition of Griffin's pioneering work, which exhibited the problems of behaviorist and cognitive thinking that fails to acknowledge conscious awareness in mammals and thinking in small animals, several researchers pushed forward the research agenda of cognitive ethology. See: Ristau, Carolyn A. (ed.) Cognitive ethology : the minds of other animals : essays in honor of Donald R. Griffin (Hillsdale, N.J. : L. Erlbaum Associates, 1991). A comprehensive discussion of the multiple views that inform the debate around cognitive ethology, including the critique of those who oppose the very foundational principles of this science, can be found in: Bekoff, M., and Allen, C. "Cognitive ethology: Slayers, skeptics, and proponents", in R. W. Mitchell, N. Thompson, and L. Miles, eds. Anthropomorphism, Anecdote, and Animals: The Emperor's New Clothes? (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1993). In his book Kinds of Minds, Daniel Clement Dennett makes a general attempt to explain consciousness irrespective of species. He takes the "intentional stance", i.e., the strategy of interpreting the behavior of something (a living or non living thing) as if it were a rational agent whose actions are determined by its beliefs and desires. He examines the "intentionality" of a molecule that replicates itself, that of a dog that mark territory, and that of a human that wishes to do something in particular. In the end, for Dennett it is our ability to use language that forms the particular mind humans have. Dennett believes that language is a way to unravel the representations in our mind and extract units of them. Without language, an animal may have exactly the same representation, but it doesn't have access to any unit of it. See: Dennett, D. C. Kinds of Minds: Toward an Understanding of Consciousness. (New York: Basic Books, 1996). For an examination of the rapport between philosophical theories of mind and empirical studies of animal cognition, see: Allen, C., & M. Bekoff. Species of Mind, The philosophy and biology of cognitive ethology (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997). Focused studies on the intelligence of non-primate species have also contributed to demonstrate the unique mental abilities of creatures such as marine mammals, birds, and ants. See: Schusterman, R. J., Thomas, J. A., and Wood, F. G. eds. Dolphin Cognition and Behavior: A comparative Approach (Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum, 1986); Skutch, A. F. The Minds of Birds (College Station, TX: Texas A. & M. University Press, 1996); Pepperberg, Irene Maxine. The Alex studies : cognitive and communicative abilities of grey parrots (Cambridge, Mass. ; London : Harvard University Press, 2000). For the question of communication in ants see Gordon, D. M. 1992. Wittgenstein and ant-watching. Biology and Philosophy 7: 13-25. On page 23, Deborah Gordon points out that "the way that scientists see animals' behavior occurs... [in] a system embedded in the social practices of a certain time and place." Gordon's field studies of interactions between neighboring colonies have shown that ants learn to recognize not only their own nest-mates but also ants from neighboring, unrelated colonies. Her field studies have led to further research concerning communication networks within ant colonies. For a more exhaustive examination of the problem, see: Gordon, D. M. . Ants at Work: how an insect society is organized. New York: Free Press, 1999). The key contribution of Gordon's book is to undue the popular perception that ant colonies run according to rigid rules and to show (based on her fieldwork with harvester ants in Arizona) that an ant society can be sophisticated and change its collective behavior as circumstances require. Finding inspiration in Charles Darwin's book The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1872), Jeffrey M. Masson and Susan McCarthy make a convincing case for animal emotion. See: Masson, J. M. and S McCarthy. When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals (New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell, 1995). On the minds of nonhuman primates, see: Cheney, D. L., and Seyfarth, R. M. How Monkeys See the World: Inside the Mind of Another Species. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990); Montgomery, S. 1991. Walking With the Great Apes: Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Birutè Galdikas. New York: SUNY Press; Savage-Rumbaugh, , S. and R. Lewin 1994. Kanzi, The ape at the brink of the human mind. New York: Wiley; Russon, A. E., K. A. Bard & s. T. Parker eds. 1996. Reaching into Thought, the Minds of the Great Apes. Cambridge U. Press; Waal, F. M. de 1997 Bonobos: The Forgotten Ape. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

9 - Buber, Martin. I and Thou (New York: Collier, 1987), p. 124. According to Michael Theunissen, "Buber sought to outline an "ontology of the between" in which individual consciousness can only be understood within the context of our relationships with others, not independent of them." See: Theunissen, Michael. The Other: Studies in the Social Ontology of Husserl, Heidegger, Sarte, and Buber. Trans. Christopher Macann. (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1984), pp. 271-272.

10 - Bakhtin, M. Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics. Trans. Caryl Emerson. (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1984), p. 270. For Bakhtin, dialogic relationships "are an almost universal phenomenon, permeating all human speech and all relationships and manifestations of human life -- in general, everything that has meaning and significance." Op.cit., p. 40.

11 - On the formation of "ego" or subjectivity through language, and the notion that it is only through language that we are conscious (i.e., are "subject" at all), see: Emile Benveniste, "Subjectivity in Language," chap. 21 in Problems in General Linguistics, trans. Mary Elizabeth Meek (1966; Coral Gables, Florida: Univ. of Miami Press, 1971), pp. 223-230. Echoing Buber, Benveniste's position is that when a person says "I" (i.e., when an individual occupies a subject position in discourse), he or she takes one's place as a member of the intersubjective community of persons. Thus, in being a subject/person, he or she is not simply an object/thing.

Benveniste was certainly not the only to consider the intersubjective nature of human experience. Wlad Godzich wrote: "For Kant, the fact that the individual could not experience the object as it was in itself required the postulation of another dimension among individuals: intersubjectivity". See: Arac, Jonathan and Godzich, Wlad (eds.) The Yale Critics: Deconstruction in America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1983), p. 46. When Edmund Husserl considered in retrospect his lectures of 1910/11, he wrote: "My lectures at Göttingen in 1910-11 already presented a first sketch of my transcendental theory of empathy, i.e. the reduction of human existence as mundane being-with-one-another to transcendental intersubjectivity." See: Husserl, E. Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and a Phenomenological Philosophy, Second Book, Phenomenological Investigations Concerning Constitution (Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1989), pg. 417. For Maurice Marleau-Ponty our not-sameness to each other is not a flaw, but is the very condition of communication: "the body of the other -- as bearer of symbolic behaviors and of the behavior of true reality -- tears itself away from being one of my phenomena, offers me the task of a true communication, and confers on my objects the new dimension of intersubjective being." For Marleau-Ponty it is in the ambiguity of intersubjectivity that our perception "wakes up." See: Merleau-Ponty, M. Primacy of Perception (Chicago: Northwestern University Press, 1964), 17-18. For a critical analysis of Merleau-Ponty's position on intersubjectivity, see: Friedman, Robert M "Merleau-Ponty's Theory of Intersubjectivity", Philosophy Today 19: 228-42 (Fall 1975). Jurgen Habermas also gave the concept of intersubjectivity a central place in his work. Giving continuation to one of the projects of the Frankfurt School (the critique of the notion that valid human knowledge is restricted to empirically testable propositions arrived at by means of systematic inquiry professed to be objective and devoid of particular interests), Habermas finds in intersubjectivity a means of opposing theories which base truth and meaning on individual consciousness. For him, intersubjectivity is a communication situation in which "the speaker and hearer, through illocutionary acts, bring about the interpersonal relationships that will allow them to achieve mutual understanding". See: Habermas, J. (1976). Some distinctions in universal pragmatics. Theory and Society, 3, (2), p. 157. Habermas further explained his view of intersubjective communication: "When a hearer accepts a speech act, an agreement comes about between at least two acting and speaking subjects. However this does not rest only on the intersubjective recognition of a single, thematically stressed validity claim. Rather, an agreement of this sort is achieved simultaneously at three levels.... It belongs to the communicative intent of the speaker (a) that he perform a speech act that is right in respect to the given normative context, so that between him and the hearer an intersubjective relation will come about which is recognized as legitimate; (b) that he make a true statement (or correct existential presuppositions), so that the hearer will accept and share the knowledge of the speaker; and (c) that he express truthfully his beliefs, intentions, feelings, desires, and the like, so that the hearer will give credence to what is said." See: Jürgen Habermas, The Theory of Communicative Action, Vol. 1 Reason and the Rationalization of Society (Boston: Beacon Press, 1984), pp. 307-308.

12 - From the perspective of his unique and systematic branch of theoretical biology, Maturana explains the notion of consensual domain with great clarity: "When two or more organisms interact recursively as structurally plastic systems, each becoming a medium for the realization of the autopoiesis of the other, the result is mutual ontogenic structural coupling. From the point of view of the observer, it is apparent that the operational effectiveness that the various modes of conduct of the structurally coupled organisms have for the realization of their autopoiesis under their reciprocal interactions is established during the history of their interactions and through their interactions. Furthermore, for an observer, the domain of interactions specified through such ontogenic structural coupling appears as a network of sequences of mutually triggering interlocked conducts that is indistinguishable from what he or she would call a consensual domain. In fact, the various conducts or behaviors involved are both arbitrary and contextual. The behaviors are arbitrary because they can have any form as long as they operate as triggering perturbations in the interactions; they are contextual because their participation in the interlocked interactions of the domain is defined only with respect to the interactions that constitute the domain. Accordingly, I shall call the domain of interlocked conducts that results from ontogenic reciprocal structural coupling between structurally plastic organisms a consensual domain." See: Maturana, Humberto R. "Biology of Language: The Epistemology of Reality", in G. Miller & E. Lenneberg (Eds.) Psychology and Biology of Language and Thought (New York: Academic Press, 1978), p. 47. For an earlier discussion of "consensual domains", see: Maturana, H. R. The organization of the living: a theory of the living organization. The International journal of Man-Machine Studies, 1975, 7, 313-332.

Still in "Biology of Language: The Epistemology of Reality", Maturana explains the term autopoiesis: "There is a class of dynamic systems that are realized, as unities, as networks of productions (and disintegrations) of components that: (a) recursively participate through their interactions in the realization of the network of productions (and disintegrations) of components that produce them; and (b) by realizing its boundaries, constitute this network of productions (and disintegrations) of components as a unity in the space they specify and in which they exist. Francisco Varela and I called such systems autopoietic systems, and autopoietic organization their organization. An autopoietic system that exists in physical space is a living system (or, more correctly, the physical space is the space that the components of living systems specify and in which they exist)". Op. cit., p. 36. See also: Maturana, H.R. & Varela, F.G. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. (Dordrecht, Holland: Boston: London : Reidel, 1980). This book was originally published in Chile as: De Maquinas y Seres Vivos, Editorial Universitaria, 1972.

13 - Emmanuel Levinas wrote: "Proximity, difference which is non-indifference, is responsibility." See Levinas, E. Otherwise than Being or Beyond Essence, translated by Alphonso Lingis (Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1981), p. 139. Partially influenced by the dialogical philosophy of Martin Buber, Levinas sought to go beyond the ethically neutral tradition of ontology through an analysis of the 'face-to-face' relation with the Other. For Levinas, the Other can not be known as such. Instead, the Other arises in relation to others, in a relationship of ethical responsibility. For Levinas, this ethical responsibility must be regarded as prior to ontology. For his insights on Buber's work, see: Levinas, E. "Martin Buber and the Theory of Knowledge", in Schilpp, P. (ed.) The philosophy of Martin Buber (La Salle, IL: Open Court , 1967), pp. 133-150.

14 - There are three types of cell: Prokaryotes, Eukaryotes, and Archae. Prokaryotes are unicellular organisms (e.g., bacteria) that lack a nuclear membrane and membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotes are unicellular (e.g., yeast) or multicellular organisms (e.g., humans) that have a nuclear membrane surrounding genetic material and numerous membrane-bound organelles dispersed in a complex cellular structure. All cells in multicellular organisms are eukaryotic. Eukaryotes include most organisms (algae, fungi, protozoa, plants, and animals) except viruses, bacteria, and blue-green algae. Another major domain of life is called Archaea, microorganisms with genetic features distinct from prokarya and eukarya. The DNA of Archea is not contained within a nucleus. Many Archae live in harsh environments, such as thermal vents in the Ocean and hot springs. Most methane-producing bacteria are actually Archae.

15 - Teleo-nomic means regulatory principle (nomic) guided by an objective or intention (teleo), without implying any vitalistic connotations. For the concept of teleonomy, see: Ayala, F., "Teleological Explanations in Evolutionary Biology" in Philosophy of Science, (1970), v. 37, pp. 1-15; Lorenz, Konrad. Foundations of Ethology (New York: Springer, 1981), pp. 23-35; Lorenz, K. Behind the Mirror (New York: London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977), pp. 21-25. Maturana and Varela advocate the "elimination of teleonomy as a defining feature of living systems", because they believe this concept does not accomplish much more than revealing "the consistency of living systems within the domain of observation". See : Maturana, H.R. & Varela, F.G. Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. (Dordrecht, Holland: Boston: London : Reidel, 1980), pp. 85-87.

16 - On the question of the welfare of transgenic animals, see: L.F.M. van Zutphen, M. van der Meer, (Eds.) Welfare Aspects of Transgenic Animals (New York: Springer, 1997).

17 - By this I mean that the process was expected to be (and in fact was) as common as any other rabbit pregnancy and birth. This is due to the fact that transgenic technology has been successfully and regularly employed in the creation of mice since 1980 and in rabbits since 1985. See: Gordon, J.W., Scargos, G.A., Plotkin, D.J., Barbosa, J.A. and Ruddle, F.R. (1980) Genetic transformation of mouse embryos by microinjection of purified DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 77, 7380-7384; Gordon, J.W. and Ruddle, F.H. (1981). Integration and stable germ line transformation of genes injected into mouse pronuclei. Science 214:1244-1246; Hammer, R. E., Pursel, V. G., Rexroad, C. E., Jr., Wall, R. J., Bolt, D. J., Ebert, K. M., Palmiter, R. D., and Brinster, R. L. Production of transgenic rabbits, sheep and pigs by microinjection. Nature 315, 680-683 (1985). The term transgenic was first used by J.W. Gordon and F.H. Ruddle in their 1981 paper. For additional information on expression of GFP in rabbits, see: Kang, T Y ; Yin, X J ; Rho, G J ; Lee, H ; Lee, H J . Cloning of transgenic rabbit embryos expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene by nuclear transplantation. Theriogenology. 53, no. 1, (2000): 222.

18 - The zygote is the cell formed by the union of two gametes. A gamete is a reproductive cell, especially a mature sperm or egg capable of fusing with a gamete of the opposite sex to produce the fertilized egg. Direct microinjection of DNA into the male pronucleus of a rabbit zygote has been the method most extensively used in the production of transgenic rabbits. As the foreign DNA integrates into the rabbit chromosomal DNA at the one-cell stage, the transgenic animal has the new DNA in every cell. For detailed discussion of the methods and applications of microinjection technology, see: Lacal, J.C., Perona, R. , and Feramisco, J. Microinjection (New York: Springer, 1999). The first successful creation of transgenic mice using pronuclear microinjection was reported in 1980: Gordon, J.W. et al., 1980. Genetic transformation of mouse embryos by microinjection of purified DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77: 7380-7384. The new gene was proven to have been integrated into the mouse genome, but it did not express. The first visible phenotypic change in transgenic mice was described in 1982 for animals expressing the rat growth hormone sequence: Palmiter, R.D. et al., 1982. Dramatic growth of mice that develop from eggs microinjected with metallothionein-growth hormone fusion genes. Nature 300: 611-615. Following transgenic mice creation, rabbits, sheep and pigs were also created (see note 17). Currently, several hundred transgenic expression papers are published each year.

19 - See note 2.

20 - A lagomorph is one of the various gnawing mammals in the order Lagomorpha, including rabbits, hares, and pikas.

21 - Krempels, Dana M., "What Do Rabbits See?" House Rabbit Society: Orange County Chapter Newsletter 5 (Summer 1996), 1. For a more comprehensive examination of vision in rabbits and other animals, see: Smythe, R.H., Vision in the Animal World, St. Martin's Press, New York (1975).

22 - In Part I of Book IX of his "The History of Animals", written ca. 350 BC, Aristotle recognized the complexity of animal emotional states: "Of the animals that are comparatively obscure and short-lived the characters or dispositions are not so obvious to recognition as are those of animals that are longer-lived. These latter animals appear to have a natural capacity corresponding to each of the passions: to cunning or simplicity, courage or timidity, to good temper or to bad, and to other similar dispositions of mind." See: Aristotle. History of Animals. Books VII-X. (Cambridge, MA: London : Harvard University Press, 1991). Although in the first chapter of the Metaphysics Aristotle attributes forms of reason and intelligence to animals, in another book (Politics) he claims that humans are the only animal capable of logos (Book VII, Part XIII): "Animals lead for the most part a life of nature, although in lesser particulars some are influenced by habit as well. Man has rational principle, in addition, and man only." Also in the Politics, he compares animals to slaves (Book I, Part V): "the use made of slaves and of tame animals is not very different; for both with their bodies minister to the needs of life. " See: Aristotle. The works of Aristotle (London, Oxford Univ., 1966).

23 - In his 1637 Discourse on the Method, Descartes insists on an absolute separation between human and animal. For him, consciousness and language create the boundary of being between humankind and animals. Descartes stated that "beasts have less reason than men," and that in fact "they have no reason at all". See: Descartes, Rene. 1637. "Discourse on the Method," in Descartes: Selected Philosophical Writings. Trans. John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff and Dugald Murdoch. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), p. 45. For Descartes, since animals do not have a recognizable language they lack reason, and as a result are in his view like automata, capable of mimicking speech but not truly able to engage in discourse that enables and supports consciousness. The byproduct of this view is the ascription of animality to the domain of the unconscious. This maneuver did not escape the attention of semiotician Charles Sander Peirce, who criticized Descartes: "Descartes was of the opinion that animals were unconscious automata. He might as well have thought that all men but himself were unconscious" See: Peirce, Charles Sanders. 1901. "Minute Logic," in Peirce on Signs: Writings on Semiotic by Charles Sanders Peirce. Ed. James Hoopes. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), p. 234.

24 - In An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Book II, Chapter XI), John Locke wrote: "If it may be doubted whether beasts compound and enlarge their ideas that way to any degree; this, I think, I may be positive in that the power of abstracting is not at all in them; and that the having of general ideas is that which puts a perfect distinction betwixt man and brutes, and is an excellency which the faculties of brutes do by no means attain to. For it is evident we observe no footsteps in them of making use of general signs for universal ideas; from which we have reason to imagine that they have not the faculty of abstracting, or making general ideas, since they have no use of words, or any other general signs." Even though Locke denied animals the faculty of abstract thought, he still did not agree with Descartes in considering animals automata. Still in the same chapter, Locke wrote: " if they [animals] have any ideas at all, and are not bare machines, (as some would have them,) we cannot deny them to have some reason." See: Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (New York: Dover, 1959), p. 208. In his partial rejection of the Cartesian theory of knowledge John Locke proposed two sources of ideas: sensation and reflection. By means of the difference between ideas of sensation and ideas of reflection, Locke distinguished man from animals: animals had certain sensory ideas and a degree of reason but no general ideas (i.e., abstraction ability) and as a result no language for their manifestation. For Locke, abstraction is firmly beyond the capacity of any animal, and its is precisely abstract thought that plays a fundamental role in forming the ideas of mixed modes, on which morality depends.